On Francois Dallegret

Autre Magazine Summer 2023

François Dallegret: Beyond the Bubble 2023

Yale School of Architecture Gallery, January 12 - May 27, 2023

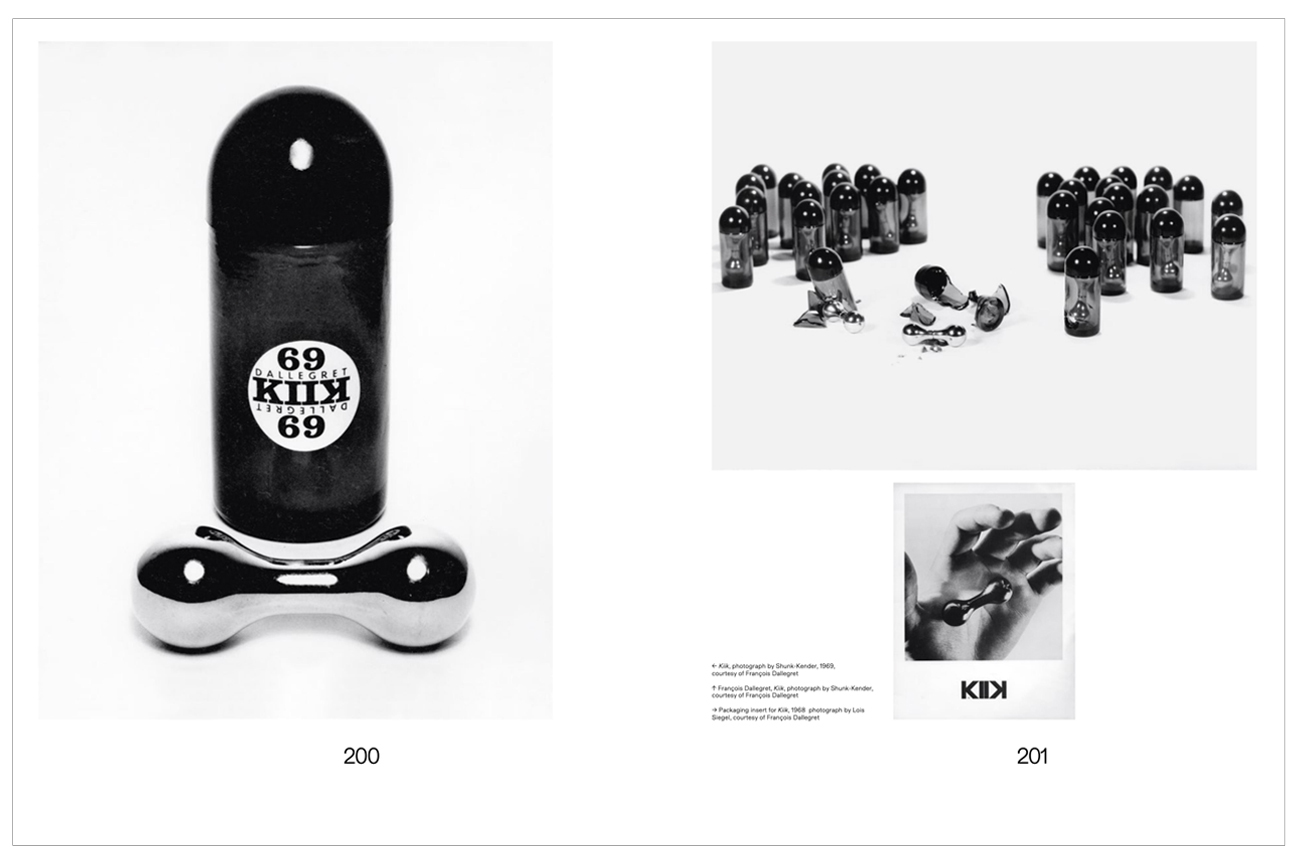

The Kiik, which was described by its creator as a “hand pill” for “breaking bad habits or starting good ones,” is a difficult thing to explain. It is a barbell shaped piece of polished stainless steel. It is two inches long, three-quarters of an inch wide, and it weighs about eight ounces (a very satisfying heft for an object of its size). It could be a pacifier or a paperweight, a sex toy or a piece of jewelry; a fidget spinner avant la lettre. I always wanted a Kiik. Once upon a time, you could buy one in the MoMA gift shop, but now they are harder to come by. I had been looking for years and last winter I finally found one, offered for a fair price by an antique dealer in Mexico City. Several weeks later, I arrived at a small shop piled with furniture on the sunny side of Avenida Obregón in Colonia Roma. The Kiik did not have its box or its original certificate of authenticity, but it was otherwise in perfect condition, gleaming inside its little brown apothecary bottle. Back on the street, I took a photograph of the Kiik in the palm of my hand and posted it online. Minutes later, my friend the Canadian artist Kara Hamilton sent me a text explaining that she had known its designer, the visionary artist François Dallegret when she was a girl growing up in Toronto. Her father, the architect Peter Hamilton, was a friend of Dallegret’s and she proposed that we reach out to him. Several months later, Kara and I arrived at Dallegret’s front door on a beautiful June morning. François greeted us with a mischievous smile at the door of the house he has shared with his wife Judith in the Westmount neighborhood of Montreal for fifty years. Over the course of the afternoon, we tested chairs and thumbed through old magazines while François pulled prints and posters, pins and prototypes from small drawers and vitrines throughout the house and from a basement full of flat-files packed with thousands of drawings and photographs. By the time we left his house, we had begun making plans for an exhibition of his work. The Kiik, a quintessentially Dallegret-ian object, began with an invitation from Reyner Banham to participate in the 18th International Design Conference in Aspen in the summer of 1968. In response, Dallegret designed a series of posters, envelopes, and folding paper hats with an attenuated barbell shape as their central motif. He then contracted the Montreal Screw Machine Company to render that shape in three dimensions, designed and trademarked a logo, and developed a system of packaging. In time, the Kiik became a prototype for a lamp, a design for a new US Dollar bill in Avant Garde magazine, a fabric pattern for Knoll, and a proposal for a public playground at the University of Chicago. This is how Dallegret works. An idea becomes first one kind of thing, then another, then another—the cycle of production is not a closed loop, but a spiral that churns out variations and multiple forms in a variety of media until that original idea becomes yet another familiar character in Dallegret’s universe. In the 1979 film, La Toile d’Araignée (The Spider’s Web) made by Jacques Giraldeau for the National Film Board of Canada, Dallegret appears surrounded by a menagerie of his own creations—Kiik, Lit Croix, Super Leo, Atomix—props in a world that is definitely more playful and more interesting than the one the rest of us occupy. One drawing in particular, The Environment-Bubble—which depicts Dallegret and Banham lounging nude in a clear plastic dome—became a touchstone for a generation of designers interested in inflatable, mobile, dynamic forms of architecture that could push back against institutions of authority and the rigid structures (both metaphorical and physical) they occupied. The first time I encountered Dallegret’s work was in a book called The Inflatable Moment: Pneumatics and Protest in ‘68 by the architectural historian Marc Dessauce. The book tells how a long history of inflatable architecture reached a climax in the politically fraught spring of 1968. At the center of the story is the Utopie Group: the trio of architects Jean Aubert, Jean-Paul Jungmann and Antoine Stinco (with help from a team of collaborators that included the philosopher and sociologist Jean Baudrillard) and their March 1968 exhibition Structures Gonflables (Inflatable Structures) at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Despite the fact that The Environment-Bubble (which appears in Part II of Dessauce’s book under the subheading “The Inflatable Realm”) was an early and important contribution to the radical architecture movement, Dallegret has always been quick to downplay his investment in politics. Unlike many of his contemporaries—designers like Archigram, Superstudio, Ant Farm, Cedric Price, GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel), Hans Hollein, Haus-Rucker-Co and Utopie—Dallegret was always more invested in spatial freedom than political dissent. While a generation of designers pushed, with increasing urgency, towards a more political form of experimental architecture, Francois maintained his focus on a world very much his own. He did not want to be a situationist or a surrealist. He did not want to be part of any scene, so he moved on. When I asked him recently how invested he was in the politics of that moment, he replied simply: “In the mid-sixties I was remote from politics. The only world I cared about was my own. And doing so many projects at once I had no time for it anyway.” Despite his disavowal of politics, there is an undeniable utopian dimension to Dallegret’s practice, his focus always fixed squarely on a future not yet entirely imaginable. One early insight into what utopia might mean in a Dallegret universe appears in a caption accompanying the 1966 publication of his project “Art Fiction” in Art in America. French architect François Dallegret imagines that soon most human activity will occur not on earth but in space. He sees the artist of this future time as a man who is, like his predecessor over the centuries, endowed with some special innate talent. This artist of the future differs from his predecessor, however, in that he creates no material objects, such as paintings or sculptures, but rather makes environments in space which induce a variety of specific sensory reactions in the people who enter them… Dallegret says, "in this future everyone will understand the artist's intention. His intention will be to create all sorts of natural and supernatural feelings we don't know about yet. It is a beautiful conception of a speculative future. When the exhibition at Yale opened, Kara asked François about his childhood in Morocco. Never one to answer a question directly, François told a long story about his parents moving from Le Bugue, a small town in the southwest of France to Morocco so his father could work with the Génie militaire on the Trans-Saharan Railroad. Every evening, François’ father would tell him the same story. The engineers would work all day laying the train track only to find the next morning that their work had been buried by the shifting sand leaving them no option but to start again—a futile struggle of technology against nature. This was, of course, just a story, but one that made a lasting impression on the younger Dallegret. As I listened to him retell it, it was clear to me that this was a remarkably apt metaphor for the Sisyphean nature of making art. The story continued several years later in a swimming pool where François and his brother would pass the stifling Moroccan afternoons. His only memory from that pool was a chameleon that would change color as it flitted from surface to surface near the pool. If it was on a red towel, it would turn red. If it was on white tile, it would turn white. If it was on brick, it would turn the color of brick. That, Dallegret claims, is how he learned to be an artist. “It showed me,” he recounted, “that I could go from one thing to another with no problem, like a chameleon.” After less than a year in New York, Dallegret made a second career-defining transition. Lured by the prospect of new design opportunities in the lead up to the Montreal World’s Fair—Expo 1967—Dallegret moved to Canada. Reflecting on the move in 1968, Dallegret told Time magazine, “New York may be where the action is, but in Montreal you can be a pioneer.” That is exactly what he did and by the spring of 1968, Dallegret was far from the political flashpoints in Paris and New York. In his first five years in Montreal, Dallegret produced a prodigious amount of work, establishing himself as a central figure in the Canadian architectural avant garde of the 1960s and 1970s. Dallegret’s first built work was Le Drug, a pharmacy-cum-discotheque in downtown Montreal commissioned by the eccentric pharmacist William Sofin. At street level, Le Drug was a glimmering geometric pharmacy with an exhibition space—Gallery Labo—where Dallegret showed works by Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Paul Thek, Arman, and others. Downstairs, Le Drug was a clinically white, sensuously sculpted underground nightclub featuring stalactite-like forms sprayed with cement and white epoxy. As with the Kiik, Dallegret produced a variety of merchandise with his sleek, black and white Le Drug logo—matchbooks, buttons, paper bags and coffee cups—which allowed Le Drug to live on well after the two years that it remained open. It was sort of an early-career Gesamtkunstwerk, combining the many facets of Dallegret’s production into a single, self-contained universe. For the show at Yale, we restored a piece called Tubula—a prototype, in Dallegret’s words, for an “automobile immobile”—that had not been exhibited for over fifty years. It was last on view, in fact, hanging from the ceiling of the Saidye Bronfman center in Montreal in that year of legendary political unrest, 1968. As we re-hung it from the massive concrete floor slab of Paul Rudolph’s Yale School of Architecture—a building which was badly damaged in a fire allegedly lit by student protestors in 1969—it was hard not to see it as an artifact of a very specific political moment. When I asked François how it felt to encounter it again and if he thought it might have a different meaning in the current political climate, he replied simply, “seeing it again I realized that Tubula is a bit like me—it floats high above all the tumult of the world below.” Even as projects like Le Drug began to be realized, Dallegret continued to push his ideas well beyond the limits of what was feasible in the moment. The Villa Ironique, for example, proposed a device that would perform a sort of architectural alchemy, collecting space junk and transforming it into usable material. The funnel form of the machine itself was a direct reference to a traditional Nova Scotia silo, but its function was re-imagined as a technology capable of collecting, transforming, and producing an 'ultimate shelter' by composting space junk. The same way, Dallegret explains, “that you might contemplate moon building out of lunar dust.” In 1982, Dallegret began Tas de Fumer, a series of photographs of a looming mound of manure near his farm in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. In each image, Dallegret attempts to domesticate the mountain of shit and straw with the addition of a single object—a column, an antenna, an umbrella, a Canadian flag. A standout in the series shows Dallegret, knee-deep in shit, emerging from behind a wooden panel door that has been jammed into the side of a straw-covered pile of manure. When I asked him if this might be characterized as a utopian work, he just laughed and said, “Well, not really, it’s just me coming out of a palace of manure and waving to crowds—a small message of hope amidst the pile of shit we are in.” The exhibition François Dallegret: Beyond the Bubble 2023, curated by Justin Beal and Kara Hamilton, opened at the Yale School of Architecture Gallery on January 12, 2023.

Dallegret was born in Morocco in 1937. In 1958 he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. After graduation, he began his career with a pair of shows at the legendary Iris Clert gallery that situated his meticulous pen and ink drawings, like Space City Astronef 732 and Litteraturomatic, in a context that included Clert artists like Jean Tinguely and Yves Klein (both of whom seem to have made an indelible imprint on Dallegret’s idea of the artist as showman). Despite this early success, Dallegret was restless. “Paris and ultimately France,” he later recounted to Alessandra Ponte, “just seemed like places to leave.” Dallegret arrived in New York on the SS France in 1963 and took up residence in the Chelsea Hotel. Soon after, he received a commission that would launch his international reputation when Art in America editor Jean Lipman invited Dallegret to collaborate with architectural historian and critic Reyner Banham on the publication of his seminal essay “A Home Is Not a House.” It was a brilliant pairing and Dallegret perfectly captured the mechanical systems—the “baroque ensemble of domestic gadgets”—that Banham imagined consuming American architecture from within.