"There are no natural disasters. There is no ecological architecture."

on Tatiana Bilbao's Sea of Cortez Research Center

Revista Plot

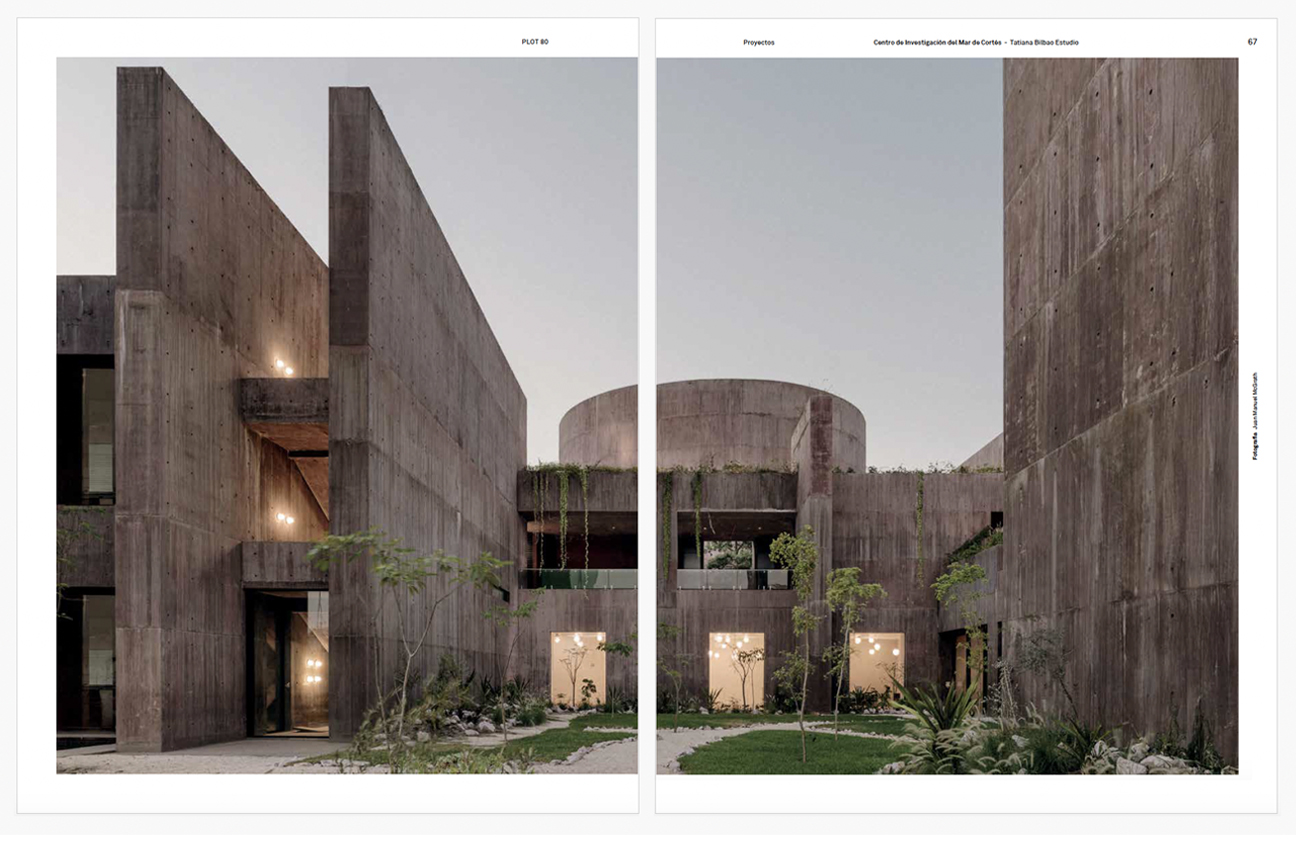

This text was originally published in Spanish in Revista Plot In April 2024, Tatiana Bilbao texted me an image of the moon passing across the midday sun in the sky over Mazatlán, Mexico. Construction had recently been completed on the Sea of Cortez Research Center, and I imagined her standing beside its circular central skylight. The building—a new aquarium—is a typology long associated with the fantasy of human control over nature. Built of concrete, a material notorious for its environmental impact, and located on the Sea of Cortez, one of the world’s most fragile and biodiverse marine ecosystems, the project should by all accounts be a bit problematic. Yet it stands as a modest triumph of architectural storytelling: a model of cautious optimism, cast in 20,000 cubic meters of pink concrete, sitting in the direct path of this rare moment of celestial alignment. At the time of the eclipse, perhaps through a subconscious awareness of forces greater than ourselves, I was reading about the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755. The event is typically remembered as a single disaster, but it was, in fact, a sequence of events—an earthquake, followed by a tsunami, followed by a devastating fire. Paintings and drawings from the period collapse the timeline, depicting crumbling facades, violent waves, and storms of fire as a single cataclysmic moment. The cumulative impact marked a turning point in the modern understanding of disaster, and an unprecedented challenge to Enlightenment optimism. Voltaire in particular struggled with the implications of such an event, questioning in his Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne how such immense suffering could occur in a world supposedly governed by reason and divine order. In a letter to Voltaire, Rousseau responded with a more pragmatic observation—had the city been less dense and its buildings more modest, the scale of the disaster might have been minimal. “Nature,” he wrote, “did not construct twenty thousand houses of six to seven stories.” It was density, not destiny, that made the Lisbon disaster a disaster. An earthquake is not a catastrophe until a city is put in its path. Or, put another way, an earthquake—like a tornado, or a flood or a hurricane—is not so much a natural disaster as an architectural one. The fallacy of the “natural disaster” has long been contested in the field of disaster studies. In their 1976 essay “Taking the Naturalness Out of Natural Disasters,” Phil O’Keefe, Ken Westgate, and Ben Wisner argued that what we call natural disasters are simply natural events that inflict outsized humanitarian or financial damage. “Without people,” they write, “there is no disaster.” The human tendency to put ourselves at the center of everything is the defining perspectival frame of the Anthropocene era. This tendency is perfectly captured in Diego Rivera’s Man, Controller of the Universe (1934)—a key point of reference for Bilbao and her team in the conception of this project. Even our most sincere fears about “destroying the planet” are self-centered, conflating an environment uninhabitable by humans with an environment incapable of sustaining life. We are damaging our ecosystem to be sure. We are reckless and cruel, but to say that we are destroying it is to grossly underestimate the resiliency of the planet. To reframe our understanding of natural disasters, we must first acknowledge the role we play in creating them. This may not be as easy as it sounds. One of the quandaries at the center of the climate crisis is the question of how humans can come to appreciate the gravity of a force for which they are largely responsible, but which is so vast and diffuse and advancing so slowly that it is nearly imperceptible to the human mind. Rob Nixon describes this as slow violence—a gradual, often invisible form of environmental harm. Tim Morton imagines climate change as a hyperobject—a phenomenon, like the internet or global capitalism, too vast in time and space to be fully comprehended. These thinkers suggest that climate change is not a crisis of knowledge, but of imagination. It’s not that we do not understand global warming—it’s that our dominant cultural and aesthetic frameworks are not equipped to render it visible. In thinking about Bilbao’s aquarium, I am particularly drawn to the argument put forward by Amitav Ghosh in The Great Derangement, which considers the failure of literature—and by extension, culture—to rise to the representational demands of the climate crisis. For Ghosh, modern literary fiction privileges individual agency and psychological realism, making it poorly equipped to handle the scale and nonhuman complexity of climate events. The “unthinkability” of our environmental crisis, he argues, is less a scientific problem than a cultural one. We are ill equipped to address climate collapse because it exceeds the imaginative horizons of our dominant forms of storytelling. Architecture, like literature, is a narrative medium. As the environmental impact of the global building industry becomes better understood, architects have found themselves in an uncomfortable position. Quantifying the environmental footprint of an entire industry is complicated, but it is now widely accepted that the built environment is accountable for about 40 percent of global greenhouse emissions. This is a huge number, surpassed only by that of the oil and gas industries, and simply put, there is no way to combat climate change without a radical reduction of energy consumption in this sector. Concrete alone is the second most consumed material on the planet after water, and it is responsible for an outsized share of global emissions (if the cement industry were a country, it would be the world’s third-largest emitter, after the U.S. and China). In much the same way that Ghosh argues that our cultural myopia renders us incapable of properly understanding the environmental crisis, our architectural imagination is limited by its own conventions. Solar panels and LEED certifications are technologies designed to maintain the status quo of capitalist consumption. We strive to design buildings that make a smaller impact on the environment, but the uncomfortable truth is that there is no such thing as ecological architecture. The best way to preserve the environment is to not build anything at all. This puts practitioners of architecture in a complicated position. Where do you begin, for example, if you are invited to design an aquarium on the Sea of Cortez? If architects want to rethink how they work, they might begin with Ghosh’s prompt to change the dominant form of storytelling, and the aquarium is an architectural typology particularly in need of a new narrative. The same year Rivera painted Man, Controller of the Universe in the Palace of Fine arts in Mexico City, Berthold Lubetkin’s modernist penguin pool opened at the London Zoo with disoriented penguins waddling skyward on spiraling concrete ramps that look like they might have been designed as test course for Italian go-carts. The energy of the design in undeniable, but so too is the force with which it imposes a Modernist fantasy of human movement on the captive flightless birds for whom it was built. In the catalog for his 2023 exhibition “Emerging Ecologies,” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curator Carson Chan described aquariums as “microcosms of how humanity endeavors to control the planet’s ecosystem.” They epitomize the dream of total control over nature, often at the expense of the animals they house. I was born shortly after the marine mammal protection act was passed in the United States and the most celebrated American aquarium at the time was the New England Aquarium—a monumental brutalist building on Central Wharf in Boston Harbor designed by Peter Chermayeff and his office Cambridge Seven Associates. It too had an iconic penguin pool, home to a beloved colony of black footed penguins from South Africa who greeted visitors as they entered the lobby. Above the penguins, a massive concrete corkscrew ramp (for humans) spiraled upwards around a cylindrical 200,000-gallon salt-water tank at the building’s center. Chermayeff’s design, which became a model for a generation of American aquariums, prioritizes human interaction with marine life, particularly the large charismatic mammals like harbor seals, bottle-nosed dolphins and the California sea lions that used to swim, even in the sweltering Massachusetts summers, in a concrete pool outside the building. In retrospect, both Lubetkin’s and Chermayeff’s designs, innovative as they may be, feel less considerate than they could have been of their captive inhabitants. In lectures and interviews, Bilbao has repeated the fact that she accepted this commission on the condition that it house no penguins. It may seem like a minor detail, but Bilbao’s decision to only work only with species endemic to the Sea of Cortez moves the aquarium’s focus away from the spectacle of the exotic and changes the proposition in a fundamental way—penguins don’t belong in Mazatlán any more than they do in in Boston or London. This initial shift became the point of departure for a narrative-based design process that began with Bilbao imagining a rising Pacific flooding central Mexico in the year 2100. As the waters slowly recede, the ruins of a building animated by decades of aquatic life are discovered by the humans who resettle Mazatlán in the year 2289. These future inhabitants find themselves in a 266-year-old structure teeming with wildlife and tangled foliage, repossessed by all manner of marine life like the carcass of a sunken ship. From this fictional future, Bilbao and her team worked backwards, opening pathways and constructing staircases to adapt an existing structure for public use. By fast-forwarding and rewinding, pushing and pulling a building through time, Bilbao collapses centuries of speculative future into a single present, rendering the imperceptible movement of climate change visible in a building that exists simultaneously in the past, present and future. It is, to borrow a phrase from the American sculptor Robert Smithson, a “ruin in reverse.” In this story, the flood is not a cataclysm, but a catalyst. The aquatic life of the Sea of Cortez has been delivered to the aquarium not by marine biologists, but by the rising tide (or so we are invited to imagine). The Sea of Cortez Research Center does not aspire to be a perfect work ecological architecture—Bilbao is smart enough to know that such a thing does not exist. Its tanks contain fish captive for human entertainment and its concrete walls hold massive amounts of embedded energy, but on the whole, her building creates a narrative that pushes back against the expectations of a what an aquarium might be by taking full advantage of the most powerful tool architects have at their disposal—storytelling. And Bilbao accomplishes all of this without sacrificing architectural form. The aquariums’ central courtyard bears a knowing resemblance to Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa Coati in Salvador, Brazil—another architectural gesture of radical optimism and an invitation to entropy rather than a resistance to it—and its simple monumentality evokes Louis Kahn’s masterful National Assembly building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Even the choice of concrete becomes defensible for a building designed to stand for centuries. By changing the timeline, by moving beyond and back into the Anthropocene, Bilbao offers a glimpse into a world without people as a first step toward a less anthropocentric architecture. In the face of climate collapse, storytelling might seem like a frivolous act, but it might also allow for a much-needed change in perspective (it should come as no surprise that takes the imagination of female architect to help man relinquish some of his control over the universe). As the Brazilian philosopher Ailton Krenak reminds us in Ideas to Postpone the End of the World, the “main reason for postponing the end of the world is so we’ve always got time for one more story. If we can make time for that, then we’ll be forever putting off the world’s demise.” Some of the ideas in the preceding text were first developed in an essay called “Architecture at the End of the World” published in Log in the summer of 2024. This text also references Rob Nixon’s Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (2011); Tim Morton’s Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World (2013); Ailton Krenak’s Ideas to Postpone the End of the World (2020); Phil O’Keefe, Ken Westgate, and Ben Wisner’s essay, “Taking the Naturalness Out of Natural Disasters” in the journal Nature (April, 1976); and Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement (2016). Voltaire’s Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne and Rousseau’s Lettre à Voltaire sur le désastre de Lisbonne, were both published in 1756. Robert Smithson’s idea of a “ruin in reverse” appears in in his 1967 essay, “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey.” Diego Rivera’s Man, Controller of the Universe was based on his mural Man at the Crossroads which was destroyed before it was completed at Rockefeller Center in New York in 1933. Cambridge Seven Associates is now CambridgeSeven.